Come along, my friends, and let’s take a little walk down Memory Lane. Join me as we journey back to the 1980s to talk about three of the most indelible memories of my childhood and how they relate to our malfunctioning country today.

Spring, 1982: Let’s start when I was in the fifth grade. I remember because it was my first year at Rock Cut Elementary, which was my fourth new school in four years. We had moved into the trailer park across the street and up the hill from the school, so it was an easy walk each morning and afternoon. And the local food bank was a short drive around the corner from the trailer park. Maybe that should have been a sign.

It was a Saturday morning the first time we went. The sky was gray, and the rain had let up but it was still clingy, the kind of warm-but-ugly 55-degree day in the spring that, after a cold northern Illinois winter, actually feels like 80. I didn’t know what we were doing until we got there and were waiting in line. It never dawned on me until right then that we were poor. I knew we didn’t have everything other people had but what we did have I thought was enough. Kid thoughts, geez. Looking back now, my dad was working three jobs because the minimum wage back then – $3.35 per hour – didn’t cut it for a family of four. To be truthful, it may be more surprising that we hadn’t been there sooner than that we had to go at all.

When it was our turn to go in, the wokers were nice with a friendly Midwestern flare and the place was clean with sparse metal shelves and a decent fill of options. Yet, it made me feel kind of shabby to be there. Even now, I drive past the low-slung brick building, setback a ways off Harlem Road, almost every year when I’m back in town for my annual visit and each time I’m in that area, it brings me down.

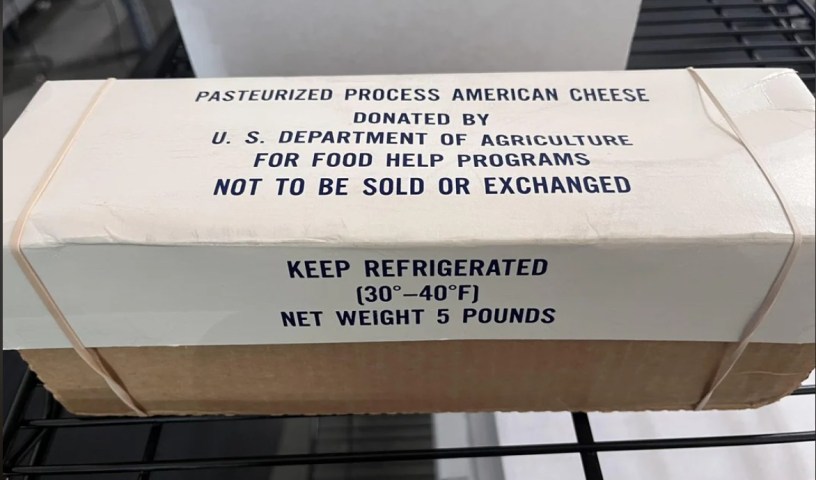

In my mind, I can still picture bringing home the boxed block cheese and the powdered milk. We ate that shit for years. Grilled cheese sandwiches. Tomato and cheese sandwiches occasionally. Grating the cheese to melt and mix with plain macaroni. It actually was pretty good. But the powdered milk, well, that was the dumbest thing I’ve ever had. Most of the time, I just drank water at home because it wasn’t worth it. But at the time, I thought we must have needed the help. Now I know, sometimes we all do.

Spring, 1985: Most Friday mornings my dad was gone to work before I left for school. We had moved earlier in the year during eighth grade, leaving the trailer park and going back to a little house we had rented before. We previously lived there when I was in fourth grade for most of the school year. It was across the street from where my step-mom’s parents lived.

When I say ‘little’ house I mean one bedroom, a living room, a kitchen, and a bathroom. There was barely room for a small table in the kitchen. That table was pushed against the ‘70s wood paneled wall and you couldn’t pull it out, there was no room for that. So no more than three people could eat there, not that we had dinners at the table often. Looking on Zillow today, that house is listed at 410 square feet. No, that number is not missing a digit. Four hundred ten. Total. Pretty much the whole house was the size of most average-sized living rooms. Keep that in mind when we come back here in my next memory.

Dad loved his coffee in the morning. I’m really surprised I never picked up the habit but am glad I didn’t. I can still smell the Folger’s filters in the trash afterward – along with the butts of his smoked Winstons — and the strong scent of his fresh pots made each morning. He was drinking a coffee when I got up and that’s when it got weird. “Have a seat for a minute,” he said.

Um, that never happened so I assumed I was in trouble. “How’s school been lately?,” he asked.

“Not bad.” I didn’t have much to say on it. First, I was 13 years old. Second, school was boring, too easy so I didn’t try much.

“Your grades have been good. Here, take this for doing a good job,” he said as he handed me a $5 bill. Barely awake me was stunned. It wasn’t my birthday or Christmas so I didn’t know why he’d give me money. He noticed. “Take it,” he said. “Buy yourself lunch at school this week.”

That worn old Lincoln, one that I knew didn’t have a matching partner in his pocket, would do exactly that. It paid for nearly a week’s worth of hot a la carte at the cafeteria, something that’d be a luxury. Classic square ‘80s lunchroom pizza and tater tots were purchased and consumed daily. I got an extra chocolate milk once or twice as well. I’m not one with great self-control so it didn’t stretch out. That $5 was gone by the following mid-week.

And then it was back to the old hot lunch routine. I’d been on the free lunch program for years. It was so normalized for me that I know there were times I made fun of some of my friends who only had “reduced” cost hot lunches, as if that as some sick burn.

Once again, having that free meal was not something that materialized in my brain as being a marker for being in need. Having that yellow punch ticket for five meals every week – assuming I didn’t wash it in my jeans and ruin it, in which case I may or may not be able to pull together enough change for lunch one or two days that week – was just the way the world worked and I was glad to have it.

Aug. 7, 1988: It’s tough to admit this but I had to go upstairs the other night and look up that date. You’d probably think I would remember the day my dad died off the top of my head, but honestly, I’m always amazed at people who keep dates like that in their brain after almost 40 years. It’s the most memorable thing from my childhood for sure. I know what happened that day; I just haven’t been able to recall the actual date for years until rummaging through a small box of old keepsakes and finding the In Memoriam from his funeral. I guess time moves on and after a certain point, you have to move on as well. At least that’s what I’ll tell myself.

I do know that that day came out of the blue. It was a Sunday and I had gotten off work a little earlier than normal. During the summers, I worked a job seal coating driveways and parking lots until high school football season started up in August. It was long hours and great money for a 16-year-old. Getting home around 5 p.m. was not usual as finishing a little before dusk was more normal.

Home now was my biological mother’s house. I was living there for the summer after moving out of my dad’s house earlier in the year. You know that 410-square-foot, one-bedroom house? Yeah, we were still living there. For a lot of reasons – mainly being that we now had six people living in that house, with four kids in the bedroom and my dad and step-mom on a hide-a-bed in the living room – it was time for me to spread my wings somewhere else.

Dad wasn’t too happy when he found out. I had packed up all my stuff and had everything in my car in the driveway when he came home from his first job to sleep a few hours before going to his next one. He asked what I was up to. My response: “I need to go. I can’t stay here anymore.” He didn’t fight me on it. That’s why it probably was so much harder a couple months later when I got the call that he’d had a heart attack. It always felt like he truly had my best interest at heart.

The day it happened, I remember standing next to the bar where the downstairs wall phone hung. He was in an ambulance and on his way to the hospital, they said. They think he had a heart attack and it would probably be good if you got over to Rockford Memorial … just in case. It’s not clear to me still to this day if I acknowledged to myself what “just in case” actually meant in the moment. By the time I got there – and trust me, it wasn’t long as I ran every red light between Machesney Park and Rockton Avenue – it was basically over. He died that night and we had a funeral on Thursday, Aug. 11, 1988. I never returned to that little house.

Why do I bring up these memories? What do they have to do with each other?

Honestly, my dad’s death has nothing to do with the others for the purpose of this story. But I’d be being disingenuous if I didn’t include it as one of the most memorable events of my childhood. It was the second-most defining life event before I became an adult, only behind me being adopted but I was too young when that happened to remember.

The reason I bring up these memories is because of where we are today. Until late on Friday, Oct. 31, when a judge said the government couldn’t stop paying SNAP benefits, our administration was trying to do exactly that. Let that sink in if you haven’t already. There are around 16 million kids – about 1 in 5 children in the United States – who were about to wake up with less food available to them than the day before ON PURPOSE.

The average SNAP benefit is $6.16 per day. That doesn’t seem like anything, right? What does that even buy? I’d tell you what but I don’t care what it buys. At all. They have been determined to have need and if it can help, then it should. What I care about is that those dollars and cents might be on the brink of being taken away from children who need it. That’s not even mentioning the millions of adults – most who do have jobs or are disabled or are caregivers – who could lose the same.

So what can we do about it? Today is not about red or blue, or picking sides. Feel free to go to my Instagram account (@_trickie_) and I’ll be glad to discuss the politics of it there all day long. If you have a willingness to actually talk about where we’re at as a country, then I encourage you to follow me. Let’s do that there though.

Here, today, my ask is simple: if you are able, pick up your wallet and donate to a local food bank right now.

Help out your neighbor.

Even if the benefits are paid out on time this time, there is still so much food insecurity in this country that it should be something we talk about daily, not just on days when the system comes crashing down around us. If you can, help that kid in need. I’ve been there. I know what it’s like to need a helping hand, even if at the time I didn’t understand so clearly. Maybe together, we can make some child’s memories less about what they didn’t have and more about how the world should work.